Gustave Besson, his Factories and Family

The purpose of this article is to give a brief history of Gustave Besson’s life and brass instrument making as accurately as possible and making clear when sources of information are primary, secondary etc. Corrections and comments are encouraged. Great help was happily given towards this effort by Niles Eldredge, Bruno Kampmann, Josh Landress, Sabine Klaus, Pascal Durieux, Tom Meacham and others.

Some of the challenges in constructing this story is that the Paris civic records from before 1860 were destroyed when the Hôtel de Ville de Paris (city hall) was burned in 1871. However, many birth, marriage and death dates were thereafter gotten from church records, and many can be found in later documents. In addition, the census records for Paris from 1872 are not available for unknown reasons. Other French records may exist, but are difficult to access and may add to this later.

Gustave Auguste Besson was born in Paris on January 20th, 1820, to Jean Auguste and Cecile Josephine Marcelin Besson. Algernon S. Rose, in his Talks with Bandsmen, reported being told in 1893 by Mr. H. Grice, the manager of the English factory that his father was a distinguished army colonel and several newspaper accounts in the 1890s state that he served with Napoleon I at Waterloo.

Details of his early work history traditionally have relied heavily on information from Besson, including that published by musicologist Constant Pierre in his 1893 Les Facteurs d’Instruments de Music les Luthiers et la Facteur Instrumentale Precis Historique: “From the age of 10, he entered an apprenticeship with (Emmanuel Jean Marie) Dujarier, then he worked in several houses, and, at 18, tormented by the desire to carry out various projects, he established himself with limited resources, which obliged him first of all to undertake only works in a manner.” The earliest source for this story found by the author was Quinze visites musicales à l'Exposition universelle de 1855 by the composer Adrien de la Fage in 1856. On his thirteenth visit, de la Fage encountered the area of the exposition that included makers of military musical instruments. The story must have been told directly by Gustave Besson and his contemporaries were available to dispute the facts.

Even if the early age of his accomplishments is exaggerated, there is likely some truth in it. Starting around 1895, company literature stated that the house of Besson was founded in 1834. Assuming that there was some reason for this claim, perhaps that is the year that Gustave Besson started his apprenticeship, at the age of 14, or after 4 years as apprentice, gained more responsibility as a maker.

An excellent list of sources is contained on the website “Luthier Vents” (Wind Instrument Makers) in French, and computer translations are more than adequate to comprehend in English. The date of the earliest address for Gustave Besson listed there and in The New Langwill Index is 1842. The Almanach-Bottin du Commerce de Paris, published in January of that year lists: “Besson, fab. Inst. de musique en cuivre, Tiquetonne 14.” The same almanac is not available for the previous year, but a similar publication, Annuaire General du Commerce does not have a listing for Besson in 1841 or earlier years. Also, the brass musical instrument makers exhibiting in the Paris Exposition National de l’Industrie de 1839 included Labbaye, Raoux, Jahn and Guichard, but not Besson.

In his Histoire Illustrée de l’Exposition Universelle published in 1855, Charles Robin states that “M. Besson was barely twenty-two years old when he was introduced to clever research and curious discoveries that earned him great consideration among his colleagues.” This also would have been 1842.

It would seem likely that he established this shop in late 1841, when he was 21 years old, in time for the listing in the Almanach. However, as indicated by Pierre above, he may have been conducting independent business from his parents’ residence or other location while still employed by Dujariez or another maker. We can assume that whatever his situation, he was gaining experience in the business.

The earliest record of Gustave Besson entering instruments into an exhibition was the “Exposition Produits de l’Industrie Française” in 1844. The report of the jury stated that he entered “un cor à pistons et un bugle…, un cor ordinaire” (a horn with valves and a bugle, a natural horn) but that they were not fully completed. The jury awarded them an honorable mention. While it might not seem wise to enter unfinished instruments, it seems to have gone well for him for a first time out.

Only five instruments are known that were made in the three years that Besson’s shop was on rue Tiquetonne: one cornet with Stölzel valves and three ophicleides. Previously unknown, Bruno Kampmann of Paris has found in Bottin’s 1845 Paris directory, a listing for Besson at 13 rue de la Bibliothèque. Bruno is working on an article to publish in the French language Larigot, the publication of l’Association des Collecctionneurs d’Instruments à Vent, where he will reveal more new discoveries. In 1846, Besson moved to rue des Trois Couronnes 7, where he must have had more space to expand the business. In his 1858 Dictionaire Universal des Contemporains (similar to “Who’s Who” in the 20th century), Louis Gustave Vapeureaux wrote that Gustave Besson recovered from bankruptcy some time between 1844 and 1851.

Besson’s cornets followed the designs of other Parisian makers, using Stölzel valves as seen above and the original form of Périnet as in the image below. “Modéle Halary” is our modern term for the earliest known cornets with Périnet valves and those made later that follow the same basic design. This subject is covered in an excellent article by Maxime and Christian Chagot, “Cornets Modéle Halary et Premiers Pistons Périnet”, published in Larigot. All of the earliest examples, made during the duration of the patent that are known, were made by Halary, and the design was used by most other French makers, including Besson, through the 1850s.

On October 16, 1847, Besson married 18 year old Florentine Mélanie Ridoux, 9 years his junior. They lived at the same address as the workshop, which was the most common practice for small businesses at the time. The same five story building on rue des Trois Couronnes, built in 1800, still exists today as 19 condominium apartments. The center of Paris was increasingly industrialized, but this building would not have had steam power in the 1840s. While a treadle lathe, powered by the operator, would have been used for light turning processes, larger lathes would have been necessary for heavier work including spinning bell flares. An additional worker would have to be employed to turn a large flywheel to power the lathe. The benefits of steam power may been a primary motivation for the move, in 1869, to 92 rue d’Angoulême.

Besson’s advertising in the 1850s included a list of honors including Médaille d’Argent, Paris 1849, presumably awarded at the Exposition Nationale des Produits de l’Industrie Agricole et Manufacturière. In the second volume of the report of the jury, published in 1850, 12 makers of brass instruments are listed with descriptions of the instruments exhibited and awards granted, but Besson is not among them. Perhaps there was another event in Paris that year in which medals were awarded that has eluded the author. He stopped making this claim in about 1860.

The sample size of existing instruments made by Besson in the years 1846 until about 1854 is too small to make many conclusions, so much of this information will be corrected in the future. This is despite the efforts of Niles Eldredge, compiling a list of all known examples. Besson seems to have started using the “GB” monogram very early, perhaps within a year at this address. Only two instruments from this address marked “Besson” don’t have it, both with rotary valves. One of those does not appear to have been made by Besson, the wording is engraved to appear to be Besson’s stamps. In addition, two cornets made by Besson in this period, but stamped “Pask & Koenig” and with Pask’s London address lack the monogram.

The earliest of the rotary valve cornets may be the earliest example of an instrument from Rue de Trois Couronnes shop not only based on the lack of monogram, but relatively crude workmanship. It seems very likely that it pre-dates the cornets with numbers stamped on the mouthpipe parts. It has a deluxe silver-plated finish and decorative engraving and leather covered case, begging speculation that it was a show piece, perhaps intended for the 1849 Paris Exposition or among the instruments shown in 1851. That would indicate a later date of manufacture, of course.

Opening on May 1, 1851, the exhibition was a very grand affair with the goal of eclipsing the previous expositions in Paris and establishing Britain as a world industrial leader. It was promoted by Prince Albert and several other influential champions of industry, and a huge greenhouse-like structure was built of cast iron and glass with three floors of exhibit space and a central atrium towering above. It was called the “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations,” mostly known as the “Crystal Palace Exhibition.”

The jurors’ report included many lines praising Adolphe Sax and his instruments but only listed other French makers including Besson. Rather than gold, silver and bronze medals, the awards were divided into “Council Medal,” “Prize Medal” and “Honorable Mention.” Besson was awarded Prize Medal for “Various metal musical instruments.” In the official catalog, published at the start of the exhibition, G.A. Besson was listed entering “Cornet-à-pistons, in brass and silver, ophicleide &c.”

After the close of the London Exhibition, the famous orchestra promoter and conductor, Louis Jullien purchased some of the instruments that had been entered by both Besson and Courtois and became the London outlet for both makers. By November, he secured the endorsement of Koenig for cornets of both and advertised widely in newspapers and other publications. While Courtois continued this relationship through 1859, by early 1855, Besson had left this arrangement. Jullien’s finances were unstable and Besson likely knew that it was temporary while he worked to establish a factory in London. No Besson instrument is known with Jullien’s name on it. In his 1893 My Musical Life and Recollections, Jules Rivière states that he provided lodging for Besson in Green Street and then located for him the property on Euston Road. This is where Besson instruments were made until 1933.

The Bessons would have observed a growing market in England for brass instruments and according to The New Langwill Index, had established an outlet in London before 1850, at the address of John Pask, an instrument dealer and possible woodwind instrument maker. Langwill also states that in about 1849, Pask was in partnership with the famous cornet soloist Hermann Koenig selling “Pask & Koenig” instruments. Josh Landress has shown that some of these were made in Paris by Besson. Others were made by another maker, likely Gautrot aîné, who was already well known as the largest supplier to retailers such as Pask. The London Gazette reported in 1851 that Pask’s partnership with Koenig was dissolved by mutual consent on April 10th that year. This was less than a month before the opening of the London Exhibition, where more than a dozen brass and woodwind instruments were entered into the exhibition under the name “Koenig & Pask.” Also in April, Philip J. Smith placed advertising in The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, claiming to be the sole agent for Besson cornets.

One of the earliest cornets made by Besson is engraved “Proved by Her Koenig” and stamped with monogram “GB” and “Pask & Besson,” Pask’s address etc. Also, a serial number “8” is stamped on the mouthpipe shank receiver in the manner of others of the earliest cornets made by Gustave Besson made in his shop on rue de Trois Couronnes. Pictured below, this cornet has original design Périnet valves, but a more modern appearance than number 3, pictured above, because the main tubing enters and exits the valve section at 90 degrees, compared with parallel, as in the latter. The “shepherd’s crook” tubing was to become almost universal in Bb cornets for almost 60 years. This was about five years before Courtois’ Nouveau Modèle” cornet that utilized this design feature, with his own unique valve designs. Niles Eldredge was able to determine that this was made no later than 1849, indicating that Pask’s partnership with Besson may predate that with Koenig and certainly overlaps. The waterkey was most likely added much later.

Like most makers, Besson did not make valves for his early production and before 1852 he used Stöltzel (cornopean) and Périnet valves that were available in Paris. The valves may have been made by François Sasaigne, who had been making Périnet valve assemblies under license until the patent expired in 1843. In 1852, valve maker Charles Edme Rödel patented an improved version of Périnet valves in which he claimed to improve the circulation of air and thus the tone of the instrument. In an addition to the patent, he states “it offers that of almost completely removing the bumps and elbows that narrowed the air column inside the instrument.” This is the same goal that other makers, including Besson seemed obsessed with. There are at least three known cornets made by Besson with Rödel’s valve design which do exhibit the very small bumps in the ports as described, although it is very difficult to determine superiority. Comparing #3, made about 1849, with “Modéle Halary” Périnet valves (see below) to #19 with Rödel’s patented valves, they are made using standard practices of the time and very similar restrictions to the bore can be seen within the piston ports. Although none of these pistons appear to have ever been damaged, this is observation of pistons with over 170 years of deterioration and not careful measurements of newly made parts.

In his own patent, granted in 1854, Besson claimed “piston of ordinary diameter two holes exactly straight…but always see the full daylight through. The third hole is curved but always full at the point that a ball of the size of the bore, passes through.” Niles Eldredge has confirmed that in Besson cornet number 4193 with the valves made according to this patent do not have the usual bumps within the bore that we see in almost all other Périnet variants. While the Rödel valves, mentioned above and later valve designs from Besson, minimized the reduction in bore within the pistons, they did not remove it completely. Indeed, 170 years of makers claiming to remove these restrictions has still not resulted in actual proof of acoustic superiority.

The next valve design patented was in 1855, seen in the images below. Staggering the height and curve of the of the inter-valve tubes allowed for easier manufacture and less restrictions in the piston ports leading from these tubes to the valve crook. Besson called the curved inter-valve tubes “perce pleine” (full bore) and the straight tubes as seen in the cornet above “perce droite” (straight [as in “tout droute”] bore). Few examples of this design are known to survive. This is one of the earliest appearances of the “FR” “Florentine Ridoux” monogram stamped on a bell, along with “BREVETÉE’, the feminine form of the word for “patented”. The stamp on the valve section, is still stamped “BREVETÉ”, but an updated stamp was used soon after. It is also the first appearance of the secondary, forward pulling, main tuning slide. The cornets were supplied with alternate slides for high pitch and low pitch. In England these came to be known as the “piano slide”; the longer slide in place to play along with the piano.

In Quinze visites musicales à l'Exposition universelle de 1855, mentioned above, de la Fage describes how Besson made tapered tubes on “mandrins prototype” (prototype mandrels made of steel) and then bent them around forms. He included such detail that we must assume that the actual tooling or excellent visual references were on display. All brass instrument maker had formed their bells on steel or iron mandrels that determined the finished dimensions for decades before this. The innovation was that Besson made steel mandrels with the finished dimensions of all the tapered parts for their instruments of all sizes. Previously the tapered tubes for all the larger instruments were determined by carefully measuring the brass sheet when cutting, but this method allowed for a variation in dimensions, more so for a less experienced worker. Besson later named their new method “Systéme Prototype” and continued to use as part of its branding long after almost all other makers were using the same methods.

De la Fage also mentioned Besson’s invention called “trombatonar,” a contrabass instrument that he said was displayed at the 1849 Paris exhibition, describing its range extending a sixth below the string contrabass. This would indicate that it had the tube length of a modern tuba in CC and likely with four valves. Adolphe Sax had already made similar contrabass instruments in BBb. Perhaps the innovation was the additional range using the forth valve. He went on to describe a series of experiments by Besson, using various materials to make bugles and other instruments, of cardboard, pottery, lead and canvas, determining that a heavy layer of papier mâché or gutta-percha formed around the mandrels were acceptable substitutes for brass. A few years later, Besson also experimented using aluminum for both the tubing and and valve parts that were intended to lighten the action. The latter was included in his 1855 patent.

Charles Robin published additional statements from Besson in 1855 in Histoire Illustrée de l’Exposition Universelle. One was that, at the 1851 exhibition, he introduced instruments that he called “système Besson” that seems to be the same design that, in her 1874 patent, Florentine Besson called “perce droite dit modèle Besson” (straight bore called Besson model) and the design seen in a few cornets made in these years. In this design, the entry to the third valve and exit from the first valve are aligned with the tubes between the valves, but are otherwise the same as previous Périnet valves. Niles Eldredge studies this patent in “Mme. F. Besson and the Early History of the Périnet Valve,” published in 2003 in The Galpin Society Journal. He clearly shows the evolution of the “Périnet” valve design, leading to what we recognize on almost all modern piston valve cornets and trumpets.

Also stated is that another of his inventions was the “ophicléide Boëhm.” We can’t be sure what this is, but seems to be associating his design with the successful flute key system designed by Theobald Boehm. This might refer to larger holes and some of the keys for the right hand, seen in the photo below, are mounted on a longitudinal rod like most of the keys on Boehm flutes. Another unique design is the E key (thumb of right hand) on the opposite side, mounted the same way and has two tone holes covered by two pads. The larger holes were to minimize the difference in sound from those closest to the bell to those furthest and many other makers adopted these ideas in later ophicleides. This design was not patented and it is not known if Besson was leading or following other makers.

During these years, Besson and other makers were involved with legal disputes with Adolphe Sax regarding Sax’s patents for brass instruments, complicated by additions to same. The story is most often simplified by indicating that Sax invented the saxhorn family in 1843 (although the name was adopted later) and expanded the concept to saxo-trombas in 1845 and other makers infringed on these patents. The story is far more complicated and beyond the scope of this article. It has been covered well elsewhere, including “Adolphe Sax: Visionary or Plagerist?” in the Historical Brass Society Journal Volume 20 - 2008 by Euginia Mitroulia and Arnold Myers, and also “Adolphe Sax’s Brasswind Production with a Focus on Saxhorns and Related Instruments” doctoral dissertation by Eugenia Mitroulia.

In his 1861 Essai sur la Factuer Instrumental, le Comte Adolphe de Pontécoulant reported that, before the proceedings had resulted in a large fine against him, Gustave applied for and was granted a legal separation from Florentine with all their property in her name (Mme G.A. Besson). He imagined him thinking: “My wife settling in the same local, and under the same name, by making it precede only the letter F will keep at home its old traffic; I will remain at the head of the manufacture as the foreman, I will finally be de facto and de jure the Queen's Husband. – And then the patents of Sax expiring, we will exploit them on the spot.” The name of the company was changed from “Besson” to “F Besson.”

The official court record, Annales de la Propriété Industrielle Aristique et Litteraire Journal de Législation, Doctrine et Jurisprudence Françaises et Etrangères en Matiere de Brevets d’Invention, Littérature, Théàtre, Musique, Beaux-Arts, Dessins, Modèles, Noms et Marques de Fabrique, published in 1860, stated that claims were filed against Besson and other makers for infringement of Sax’s patents of 1843 and 1845 starting in 1854. Due to the complicated nature of instruments on both sides and ill-defined designs, it continued for years and a portion of the 1843 patent was nullified. Instruments and mandrels used in manufacture were confiscated from Besson and he filed suit against Sax. This was dismissed by a judge.

The 1843 patent expired in 1858 and the strongest point of Sax’s case was that his saxo-tromba patent was first to show instruments with the bell, valves and slide tubes all parallel. Less strong, but successful was his stated dimensions of the instruments in that patent. In 1858, Sax made renewed efforts in prosecution and in April, Besson was fined 2114 francs and, based on a French patent law instituted in July, 1844, an additional 2000 francs. In 1859, Gautrot, the largest maker targeted by the suits, paid 500,000 francs to settle with Sax, which was equivalent to about $250,000 then and over $8 million today. Besson took up residence at 198 Euston Road in London by 1858, where a shop building was built at the rear on an access road.

Despite separation and careers in two countries, Gustave and Florentine continued to live as a family and all four of their children were born in Paris: Cecile Henriette (1849), Marthe Josephine (1853), Georges Clement Hyacinthe (1859) and Gabrielle Augustine (1860). Oddly, the 1861 census listed only 12-year-old Cecile living with the couple in London. Gabrielle would have been under two years old. Also listed as residents in the Besson household were two employees of the firm that were from France and the census also indicated that the company employed “10 men and 1 boy.”

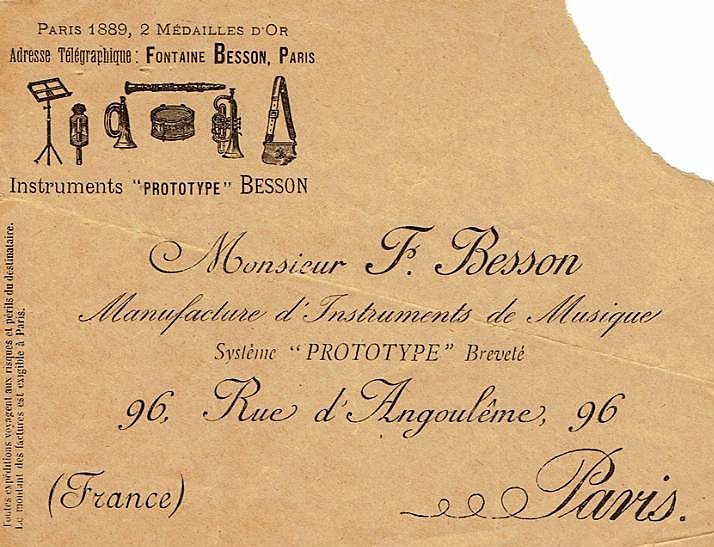

The 1871 London census lists the family, except Gabrielle, who would have been about 11 at the time, perhaps in Paris with a nanny. Cecile, 22, and Marthe, 18, were both listed as “Assistant to Musical Inst. Maker.” We know that the Besson family was also living at 96 rue d’Angouleme based on birth, marriage and death records. Travelling from one home to the other would have been an all-day ordeal.

Along with the very popular cornets and saxhorns, Besson produced a full line of brass instruments including trumpets and trombones. In the rest of this article, an attempt will be made to represent all the known cornet and trumpet designs and when they were made. Almost all this comes from the work done by Niles Eldredge in the last 30 years. This is a work in progress that will be updated as new information and surviving instruments are discovered. Some different model names used in Paris and London, including obscure model names used in the London stock books and in advertising. Anomalies seen in surviving instruments may have been produced in numbers or been built to a special order. The next several paragraphs cover in detail Mme. Florentine Besson’s patent of 1867 and additions to it in 1872, but it is possible that the drawings were made of a prototype instrument and changes were made when put into production.

In this patent, Mme. Besson presented a number of new designs, more wide-ranging than the previous patents which covered just valve designs. In the first page of illustrations, fig. 1-12, is her “nouvelle trompette aigué” (new high-pitched trumpet), was principally to be played in C with shank and crooks for B, Bb, A and Ab. It also had a shorter tuning slide for D and Db, and came with a bit/adaptor to use a cornet mouthpiece. She called this a “trompette-cornet” that can be played by cornet players without adjusting their embouchures and still produce the sound of a trumpet. No examples of this instrument are known to exist from the early years, but one is known that is made in the 1890s, and with the valve design design as in the cornet described below. Neither the shank nor tuning slide are original with this instrument and it isn’t in playable condition, but it does appear to answer to the description in the patent.

The cornet illustrated, fig. 17 and 18, and associated tuning slides fig. 19, 20 and 21, is intended to play primarily in Bb, but inserting alternate, shorter tuning slide, tunes it to C. Niles Eldredge has pointed out that this is the first illustration of this valve configuration in patent specifications, but had been produced for over a decade by then. An early example is in the Musee de la Musique in Paris with perce pleine, made about1855. She calls these cornets “forme Besson”, although it isn’t clear if this describes the valve port layout or that of the overall instrument. She also called it “Jupiter-étoile”. Aside from here, Niles Eldredge has only seen this term in the English stock books. The trombone valve sections, fig. 13 through 15, show the same valve design, with a fourth valve. The descriptions states that these can also be applied to instruments with bells upright. The text neglects to clarify fig. 16, but they seem to show two different extensions for lowering the pitch. The cornet/trumpet valve sections, fig. 22 through 33, exhibit a compensating system. When the fourth piston is depressed, lowering the cornet by a semi-tone, the first and third valve slides are also extended, compensating for the lower pitch. This idea was revisited many years later, with much success, by Lyon & Healy, C.G. Conn and others. Some years later, Besson made another design to accomplish this, with two lengths of slides for each valve, similar to other compensating systems, such as the Victory and Enharmonic cornets covered later in this article.

Most trumpets were pitched in G or F and used for military or other signal purposes, but there was a smaller demand for the instrument with valves for use in symphony orchestras and wind bands that were the equivalent of the brass band movement, called “l’orchestre d’harmonie” in France. In the second page of illustrations with this patent, fig. 34 through 36, are “trompettes d’ordonnance” or field trumpets, and valve trumpets that use the same bell and mouthpipe design, thus retaining the sound of the field trumpet. In valve trumpet fig. 35, the key is changed from F to E and Eb by substituting longer sides for the forward facing tuning slide and to D with a longer slide for the rear facing slide. Fig. 36. is a related valve trumpet with the key change using terminal crooks in the traditional way.

Fig. 54 through 60 show another idea for adding valves to a simple trumpet with an assembly that interchanges with the tuning slide. This was not a new idea; slides with two Stölzel were made to fit trumpets and horns by the 1840s. Fig. 58 she describes as a cavalry fanfare trumpet in Eb, but specifies that a valve set, like that in fig. 54 through 56, can be made to fit any simple trumpet or bugle. Fig. 59 and 60 show the same trumpet with the valve section in place. In London, in 1855, Henry Distin had patented a similar idea, in which a three piston valve assembly interchanged with the tuning mouthpipe in British pattern duty bugles.

Fig. 37 through 39 is a group of three trumpets that show a distinct evolutionary step to the modern Bb trumpet with piston valves. The features already seen here are a single 180 loop of the tube and with the tuning slide extending away from the performer. Mme. Besson stated that these are a new family of trumpets that are called “à forme longue” (with long form) and eliminates the possibility of the tuning slide hitting the player’s chin if extended too far. The first, fig. 37, is a trumpet is pitched in G, although with a shorter tuning slide for Ab. It was described as being equipped with the customary crooks for lower pitches. These would be at least to D, but as low as Bb. Fig. 38 is a trumpet in C that can be crooked down to Ab. Translated to English, she states: “This trumpet is created in proportions that allow it to be used at will, either as a trumpet or as a cornet, by the change of conical tones (shanks and crooks) for the cornet mouthpiece and cylindrical tones for the trumpet mouthpiece; in a word, this instrument is a cornet-trumpet”. Fig. 39 is a high trumpet in Eb, with a shorter slide to play in E and was equipped with crooks to C. As with the C trumpet, it could be had with conical shanks and crooks for a cornet mouthpiece or cylindrical, for trumpet. Here she also states that fig. 37 and 38 are shown as modèle anglais, with the valves between the mouthpipe and bell, but could be made in either modèle anglais or modèle français. It’s especially interesting that these two are represented as English models, which later became universal. Courtois had established the English model as the most popular design in cornet in the 1850s, and Mme. Besson had the foresight to present her most innovative trumpets in this mode. Niles Eldredge states that this is the earliest use of those terms to delineate the two styles.

Fig. 40 to 43 are a design for a trombone valve section that follows the lines of the slide section, so that it can be held by the player in the same way as a slide trombone. Fig. 53 is a cleaning rod (for holding a cleaning swab) that contains within it a screw driver and containers for grease and oil. Fig. 52 is a music lyre with a “bayonet stop”, which is a small lever that pivots to push on the touch piece of the clamp lever to hold the music book more firmly.

Fig. 44 though 51 show a pocket cornet, which Mme. Besson calls “L’Exigu, réel petit cornet à pistons de poche” (real small pocket valve cornet) and its parts. In modern French, “exigu” is used to mean “cramped” or “inadequate”. Perhaps it had a different emphasis 150 years ago, as in the English word “exiguous”, which means “very small in size”. She described it to have the same proportions as her standard size Bb cornets, “made from the same prototypes”. It is in Bb and can be extended to A with either the longer slide, fig. 49, or shank, fig. 50, the former that better preserved the small character of the instrument. It could also be made in C.

The most noteworthy of the designs in the 1867/1872 patent, are the “cornet-trumpets”. Almost all modern piston valve trumpets in contralto Bb and higher follow this model, although with fixed mouthpipes. Judging by the lack of extant instruments of this design, there must not have been many produced, but during the next two decades, the small trumpets in C and Bb found more favor. This isn’t surprising, being more familiar to cornet players. Like cornets, these trumpets, as presented in this patent, were equipped with mouthpipe shanks and crooks for additional keys, but by about 1890, Besson introduced C and Bb trumpets with fixed mouthpipes as we are accustomed to today. There is more evidence for the origin of this design, again from the research of Niles Eldredge that will take more work to make firm statements. The photo below is a very rare example of a Besson Bb trumpet made about 1891 that could be mistaken for one made in the 1930s or much later.

Florentine Besson’s description of her new trumpets and cornets in the 1867/1872 patent can be understood to express her ideas of what will find an edge in the competitive marketplace. She may be equivocal in much of this text, but very clear on the importance of proportions, notwithstanding forms. Her “trompette-cornet” in figures 1 through 12 above, she describes as preserving the tonal qualities of a simple (valveless) trompette d’harmonie, the natural trumpet that was used for playing musical pieces along with other instruments rather than the trompette d’ordonnance, which is strictly a signal instrument. She allows that it can be played with a cornet mouthpiece adapted to fit the trumpet mouthpipe, but maintains the basic character of the trumpet. The contrast may seem slight, but she states that her “cornet-trumpet”, figures 37, 38 and 39, has proportions that allow use as a trumpet with cylindrical crooks with trumpet mouthpiece and as a cornet with conical crooks with cornet mouthpiece. Unfortunately, none of these instruments are available to measure and compare, but we can at least make a start in this project by comparing the 1891 Bb trumpet featured above to cornets and other trumpets. Even if it has a different bell design than any of the three cornet-trumpets, it can be seen as the next iteration of Besson’s cornet-trumpet.

Below are four charts showing some of those comparisons. The 1891 trumpet bell appears to have been made on the same bell mandrel as the sample cornets made in 1875 and 1880. It is also very close, but not identical to two different Besson trumpet bell designs from the 1930s and another 1870s cornet. There is much more work to be done in cataloging the various bell designs that Besson made and how they were used. The evidence available, including Madam Besson’s descriptions indicate that the modern trumpet was designed with the proportions taken more from the family of cornets, not the previous trumpets.

In the early 1870s, Besson introduced another slight variation of the valve port designs for the English Model cornets without patenting it. It was originally called the “Dessideratum”. The photos below show them applied to an echo cornet, but it was most widely used in Bb and C cornets and trumpets as seen in the 1891 trumpet pictured above. It was produced in both perce droit (inter-valve tubes straight) and perce pleine (inter-valve tubes curved). About the same time (early 1870s), Besson began stamping a star on the bell and within the oval cartouche on the second valve casing. This indicated the highest quality and those without the star were sold at a lower price. This design is most interesting in that it became the “modern” cornet and trumpet valve design, still the most common today (most with perce droit).

The next new valve design, patented in 1874, was destined to become the most common of Besson cornets in British brass bands until the early 20th century, as well as those imported to the US by Carl Fischer in New York. This is evidenced by being the most numerous among the survivors from between the early 1880s and about 1910. This model was originally called “Nouvelle Etoile” (New Star) and had a star stamped on the bell and valve section. The valve port design was the same as the Desideratum presented above, with the position of the main tube entrance and the third slide tubes switched from right to left. Mme. Besson stated that this improved access to the high/low pitch slide. By 1910, it had become known as “Desideratum” and the original Desideratum, as described above, became known as the “Concertiste”. When introduced, it was also made in French models, with the bell on the right. Unlike their other French models, the first valve slide was also on the right and the bell exited the valve on the left. This is clearly seen in the British patent drawings presented below, along with the path of the air column through the valves indicated with double dashed lines. The patent was issued in France, Belgium and Britain at the same time. These images are courtesy of Jacques Cools, editor of Larigot, via Niles Eldredge.

In 1872, Besson started making cornets with valve sections that were closer to the original Périnet design, with inter-valve tubes straight across from each other. They had the general appearance as the Desideratum and Etoile models, but were not stamped with the star and were sold at lower prices. It was simply called “Périnet” in the London stock books and likely the same in Paris. Another version with the main tuning slide between the third valve and bell, was called “Ordinary Model” in London and “Cornet Belge” in Paris.

Gustave Besson’s death date has been stated as 1873 or 1874 in almost all previous sources, but his death was recorded on August 10th, 1875, in Ghent, East Flanders (Belgium). This document states that he died there the day before (August 9th, 1875). It is not known if he was there on business or some other reason. Ghent is about 35 miles from Brussels and about 185 miles from Paris and not a direct route to London. He was 55 years old.

Florentine and her daughters headed the two factories for another two years until her death in 1877, at 48 years old. Her death is even more mysterious. The declaration was made on November 5th of that year, but states that she was “deceased at a date that the witnesses could not make us know, but that seems to go back to last October 22nd, in the boundaries of St Denis (seine); there, she was brought to the Morgue #2; domiciled rue d’Angouleme no. 92.” Sainte-Denis was about five miles from her Paris home and factory. The London Principal Probate Registry of 1877 granted Florentine’s effects “Under £4,000” to Marthe “Daughter and one of the Next of Kin,” indicating that she was the more capable or trusted of the four children. A later handwritten note states “Resworn June 1881 under £8,000”. She had no will and the second entry, with a four year delay, seems to indicate that there was complication in settling the estate. Additional probate records have not been found. The amounts stated were limits that determined tax rates, so the final value of the estate was between £4,000 and £8,000.

Thereafter, the Paris and London factories were managed by Marthe and Cecile. The 1881 census in England lists the residents of 198 Euston Road as Adolphe Fontaine, Attaché to the French Consulate, Marthe, their one-year-old daughter Gabrielle, Marthe’s sister Gabrielle, her mother-in-law Marie Fontaine, two servants and an artist painter. Later evidence indicates that Adolphe did not have diplomatic duties, but called by some a clerk at the consulate. Of great interest, the census also states that the factory employed 20 men. The elder Gabrielle died in 1886, less than three years after getting married. Her involvement in the business is unknown.

There’s no evidence that Georges was ever involved in musical instrument making either. The 1881 census shows him living as a country gentleman in Hampshire (“Freehold houses and Land Owner, employing six men” as well as four servants and horses). The record of the baptism of his daughter Ruth on January 7th, 1894 and London postal directory, 1895, indicate that he was living in St. John’s Wood, London working as a “Traveller” (travelling salesman?) just two miles from the Besson factory. Notes From the High Court of Justice in 1894 indicate G. Besson and Co., boot polish manufacturer at Georges’ address, filed for bankruptcy. Paris civil records state that he died in Paris in 1905.

A little more has been found regarding oldest sister Cécile’s activities. There are no records indicating that she ever got married and three sources indicate that she headed the Paris factory in the 1880s. Evidence submitted (December 5, 1895) in the court case “Fontaine Besson vs Fontaine Besson,” states that since Cécile was entitled to a share in the business and that she would manage the Paris factory. This seems to have started shortly after Marthe’s marriage in 1879 or possibly 1881, when the estate was settled. At that time they fired managers that had been overseeing both factories. Georges and Gabrielle were bought out in 1882, leaving Cécile and Marthe as equal partners. Proceedings were initiated in 1887, presumably by Marthe, to dissolve that partnership and the next year, the court ordered that the business be sold with half the proceeds going to each sister. Marthe bought the entire business for £23,719, including a cheque from Adolphe in the amount of £7500, presumably from investments made after marriage.

In an article published in the December 1910 issue of Musica, a Paris music magazine, titled “Le Cult d’une Grande et Belle Famille de Musiciens,” Victor Lefévre, wrote: “And in 1885 Miss Cecile Besson was appointed member of the jury at the Universal Exhibition in Antwerp. This was the first time that such an honor went to a woman in an industrial and artistic part like the one we are interested in.”. Also, Belgian trademark number 2576, for the familiar bell stamp for F Besson including the “FR” monogram (Florentine Ridoux) and the feminine “BREVETÉE, that was granted to Cécile in 1887. Notice also, that the oval with “F. BESSON / (Crown or Star) / BTÉ S.G.D.G.” The oval with a crown was stamped on the second valve casings of less expensive models and the star was only stamped on the most expensive. This stamp with the crown was first used by Gustave Besson in about 1857, including on several presentation instruments, and may have originally had a different meaning. The star first appeared after the move to rue d’Angoulème in 1869, very shortly after its first appearance stamped on a bell.

We don’t know how long Cecile was in Belgium or how often she visited, but she also visited with Victor-Charles Mahillon and gave him three Besson cornets for his research collection in 1887. Mahillon had been acquiring examples of brass instruments from makers all over the world, including the United States, to study both the manufacturing details, designs and acoustics. His collection is now in the Brussels Musical Instrument Museum. She may have recognized the importance of the Belgian and Dutch markets during her time at Antwerp’s Exhibition. And she must have understood the importance in Mahillon’s studies to have had her factory produce the special cornets as a gift. While these three cornets were all made in 1887 and have serial numbers reflecting that year of production, they are made to Besson’s designs that were discontinued many years before. All details are correct for the original designs, including braces, finger hooks, pull knobs and finger buttons. The bell stamps are also correct for the designs, including the “GB” monogram, address, etc. The earliest design is with the 1854 patent. While Besson continued producing this design, with updated brace, hook, knob and button design, this specially made cornet reverted back to those from 30 years previous. The other two have two versions of what we call the 1867 design, illustrated in the patent of that year. One is the earlier version that had been made since the 1850s, with perce pleine (curved inter-valve tubes) and the other with perce droit from the time of the patent. Besson’s C and Bb trumpets with fixed, tapered mouthpipes originated about this time and the design may have been given to, or suggested to, Cecille by Mahillon during this visit. More research is ongoing into the facts of this possibility.

Cécile lived just over a mile from the factory in Paris at the time of her death, at forty years old, in 1889. The record of her death describes her as “rentiére,” a person of independent means living on funds from investments or trust. As we know, she had been bought out of the business the previous year. Cécile’s estate was valued in the London Probate Registry at £17,400, the equivalent of over £2,000,000 today.

Cécile’s will made in 1887 gave 28,500 francs to various people, including 1500 francs for an annuity for the benefit of Georges children and 10,000 francs for the benefit of the workers in the French factory. This was £1127 (Swedish krona basis), 7% of her estates value. However, her will also specified that both the London and Paris factories be sold to settle the estate. It tells of great difficulties with all three of her siblings, including her view of Marthe’s actions leading to removing her from the business: (Marthe) “odiously frustrated me, in my rights as well for the succession of my parents as for our commercial partnership she gave proof in the proceedings now pending in England.” This was less than two years before Cécile’s death.

Marthe married Adolphe Honoré Gabriel Fontaine, reputed attaché to the French consulate in London, in 1879 and both started using the name “Fontaine-Besson.” He was 10 years her senior and the marriage was a troubled one based on press accounts. These can be read on Luthier Vents website and elsewhere on the internet. Before marriage, Adolphe promised in writing, that he would have nothing to do with running the business, playing the part of “Prince Consort to the Republic” and to help in his capacity at the consulate. However, it is likely that it was his influence that resulted in the firing of the factory managers in 1881. In 1882, he was involved in founding the French Chamber of Commerce in London and gained the title of honorary chancellor. He left the employ of the consulate in 1886.

Some time before the Paris Exposition in 1889, Adolphe became more involved in publicizing the business and changed the name of the company in advertising and press release from “F (Florentine) Besson” to “Fontaine-Besson.” He claimed credit for designing newly introduced instruments including the widely publicized Cornophone (Cornon) and Clarinette Pédal. We can’t know what involvement he might have had, but there is much room for doubt, evidenced in testimony he later gave in court (1895). When asked when he learned the business of making musical instruments, his response was: “It is no matter. Was it necessary for me to know how to make a musical instrument? I do not suppose Mr. Colman makes mustard himself.”

Both Marthe and Adolphe travelled to Chicago for the World’s Columbia Exposition which opened in May, 1893. In July, Marthe took an excursion train to La Porte, Texas, where she purchased 22 lots in the new city and an additional 510 acres. At the end of the fair, Adolphe returned to Paris, but Marthe stayed for another month or so. She visited Carl Fischer, Besson’s US distributor in New York and while there, met with a reporter from the Paris newspaper l’Enevement (in English “the Event”). She told him that her plans were to build a city in Texas called “Bessonville” and a factory to supply North, Central and South America with musical instruments. Information published in Jocelyn Howell’s dissertation indicate that these markets were already becoming important to the company.

After her return, Marthe and Adolphe quarreled and in January, 1894, she sued for divorce in Paris, but not before warning her Paris employees that Adolphe was not well. She then returned to London. Paris newspapers, including La Presse, reported that Adolphe had alienated the workers by attempting to manage the factory for the first time starting in January. Previously, he had only been a figurehead, with Marthe and the foremen to oversee the factory operation.

During these months, there were daily struggles with workers and loss of customers. Adolphe cut the wages of the Paris workers twice, resulting in a strike in September. When approached by the shop foremen, he refused to meet with them and locked them out. The employees pleaded to Marthe for her return, which she did in October and convinced them to go back to work. Even though reported in at least six Paris newspapers, there was no mention of whether or not the previous wage rates were restored. It is difficult to parse the truth from press reports, the French papers were sympathetic to the workers and Marthe, and the English papers had bold headlines about her scandalous actions. On October 30th, a divorce court judge (in Paris) ruled that she had no standing to remove Adolphe from authority over their community property. She was unable to prove negligence, impairment or wickedness, which were the requirements for that decision.

In early 1895, Marthe found a buyer for the London factory and moved their belongings from the house. When Adolphe learned this in July, he told customers to stop doing business with the London branch and filed civil charges against her in England, including an injunction keeping her from accessing bank accounts. In August, she fled the country with 15 year old Gabrielle and her lover (reported as an employee, either “traveler” or clerk from Spain) with securities and other property. Several press reports stated that her intention was to live in America. Adolphe then had criminal charges filed and she was arrested in Spain and brought back for trial, arriving in London on November 21st.

Court testimony indicated that before meeting Marthe, Adolphe had no property and was living with and supported by a dress maker in London. He claimed that, since the marriage was in France, the English property was part of the (marriage) community as well. According to French law at that time, all property acquired during the marriage, including by inheritance, became that of the community and the man had sole authority over that community. When they married, the business was still owned by the estate of her mother, who had died two years before. It then became community property when she inherited it in 1881. French law also prevented a woman from doing business without the permission of her husband. When asked in court “Do you claim ownership of the goodwill, name, inventions, and everything?,” his response was: “Yes, that is the French law, and you can’t change it.”

Criminal charges were dismissed in February, 1896. Even after her ownership of the English property was settled in the courts and the sale was finalized, he continued to claim ownership of Besson in France. In a 1906 advertisement in Directory of Artists and Dramatic and Musical Education, he claimed he “holds many honorary distinctions and after 66 medals and diplomas of honor obtained in international exhibitions, he won the Grand Prix at the following exhibitions in Paris 1900, St -Louis 1904, Liege 1905.” There was no additional press coverage of worker relations at Besson, Paris. We must assume that Marthe and their employees tolerated the situation for the rest of her life so that the business would eventually go to her heirs.

When Marthe died on the 15th of September 1908, she was living near Russell Square in London, less than a mile from her old home and factory. Adolphe died in Paris just a month later. In her will probated in England in December, Marthe left her estate in three equal parts to her daughters (Marthe) Gabrielle Durand and Méha Fondere and the third part to “Cisco Besson (my son or reputed son).” Her grave memorial includes an added panel memorializing Frank Besson Flight Lieutenant, Royal Navy. He died while on a reconnaissance flight when his Nieuport 10 biplane went down due to engine failure on December 20th, 1915 off of Gallipoli in the Dardanelle Straight. He had turned 20 four days before. His London Probate record indicated that his legal name was Francisco Besson.

London’s probate record valued Marthe’s effects at the time of her death over £46,610, well over £5,500,000 today and put it in the control of Albert Durand, a civil judge and public trustee in Reims, France, who was also the husband of her daughter Marthe Gabrielle. A codicil to her will also specified that £1000 was given to Albert Durand before the rest of the estate was divided. The estate must not have been fully settled for several years, evidenced by a story published in the Houston Post, August 20, 1911, stating that an executor of Marthe Besson’s estate was sent to La Porte, Texas to establish her ownership of real estate there.

Marthe’s death left the charge of the Paris factory in the hands of her younger daughter Méha Pauline Henriette Fondère (born March 29, 1885). She was a widow at the time with a daughter, Lydie Marthe Henriette who was under two years old. She married León Alfred Sabatier in 1912. It is believed that Méha was still involved with the company after World War Two, but that’s a topic for future study.

After the sale of the London factory in 1896, its name was changed to “Besson & Company”. They had been advertising as “F. Besson & Co.”, since the early 1880s, but not marked as such on the instruments. Model designs began to diverge between the two factories. London had already introduced the Victory model compensating cornets, euphoniums and tubas in 1890, which was a slight redesign of the compensating system that had been made by Boosey & Co. since 1879. The compensating valve section was soon redesigned and the cornets and trumpets were known as “Enharmonic” models. By 1907, Besson & Co. were producing cornets with fixed mouthpipes. The “New Creation” had the valve design as in the original Desideratum, now called Concertiste. As stated above, this basic valve design is seen in all modern cornets and trumpets. The “Proteano New Creation” had the valve section, originally called “New Etoile”, now called “Desideratum” in Paris. The new English trumpets that were from Marthe’s cornet-trumpet, and had smaller bells, resulting in brighter timbre.

In Paris, Besson continued to concentrate on older models. This choice may have resulted in a contraction of production, while the London factory continued to grow. Most of the English factories output was for the brass band market and export to the USA. The latter accounted for more than one quarter of their production. What was changing in Paris was an increase in demand for the Bb and C trumpets. They became the bulk of their production in the 1920s and 1930s and were played by a large share of serious trumpet players in France and the United States.

No Besson catalogs are known to exist from before 1893. In that year, Besson’s products were included in the catalog of Les Fils d’Eugène Thibouville. All of the other instruments are presented in this 22 page catalog as if they were made by Thibouville, but most, if not all the brass instruments were made by other French makers including Gautrot, Lecomte and Sudre. As seen below, the Besson instruments are identified by name. The engraved images of the Besson cornets in this catalog range from good to terrible. It does help clarify the models listed 2, 3, 4 and 6 and matching the known dates of patent or introduction. This corroborates the cornets listed under the same numbers in the 1910 catalog that we consider later.

Less expensive versions of some of the popular cornets were offered with guarantees covering six and eight years. Ten year guarantees were given for the most expensive instruments. These were stamped with a star (etoile) on the bells and second valve casings and had water-keys as standard equipment. Water-keys were available at extra cost on the non-star cornets. The number 2 cornet was introduced in 1872 with a valve design very similar to the original Périnet piston valves. It was the least expensive option to Besson’s top quality instruments, and guaranteed for only 6 years. They continued making the models patented in 1854 and 1855, warranted for 8 years and sold at an intermediate price. Number 6 is the “Nouvelle Etoile” patented by Florentine Besson in 1874, was the most expensive of the French models, and guaranteed for 10 years. 7, the “Soliste”, was introduced in 1889 at a price almost as high as the French model Nouvelle Etoile. It utilizes the same valve design as their least expensive number 2 cornet. but guaranteed for 8 years. The image depicts it as a mirror image, or left handed cornet, unknown among survivors.

Cornets numbers 8 and 9 suffer ambiguity as presented here. The image for 8, the Desideratum, clearly shows the third valve tubing on the left side of the valve, as it was when first introduced in 1874. There is no image for 9, the Concertiste, and we don’t know for sure if it is the same as the cornet by that name that you will see in the 1910 catalog. It seems unlikely that it is the same as the English model of the Nouvelle Etoile specified in the patent. The author posits that the name had already been changed for their two most popular products and they used a distorted image of the 1874 Desideratum (English model) to represent the 1893 cornet by that name. These two cornets were guaranteed for ten years.

Next on the price list are the “Cornets spéciaux”, all guaranteed for 10 years and with the star stamped on the bells and second valve casing. Number 10, “cornet de poche” (pocket cornet) was a newer version of the “exigu”, number 11 in this catalog. The latter is described and illustrated in the 1867 patent above. The poche was a slightly longer version of the exigu and made only in Bb/A. There are examples of the exigu in Bb, C and Eb surviving. At least one cornet de poche survives from the late 1930s with original alternate shanks for playing with cornet or trumpet mouthpieces, continuing the concept established by Florentine Besson in the 1867 patent. Cornets exigu are known both in the French model (bell on right) and English (bell on left of valves).

12. soprano in Eb.

Numbers 13 and 14 are cornets in C, French and English models respectively., with slide extension for Bb and longer mouthpipe shank for B natural (with C slide) or A (with Bb extension). 15 is a Bb cornet with fourth piston valve which is a whole step ascending, raising the pitch to C (B natural with A shank in place). 16 and 17 were, again, French or English model C cornets, with alternate tuning slides with rotary valves for changing the pitch to Bb and mouthpipe shanks for C/B natural and Bb/A. Number 18 came with a tuning slide with two rotary valves, which would select all of those pitches without changing to the longer mouthpipe shank.

19 is a cornet with a fourth piston valve which would divert the air column to an echo (muted) bell. These were available in both C or Bb, only in the English model. Very few surviving echo cornets are pitched in Bb.

Under “Trompettes d’Harmonie”, number 47, “simple, tous les tons”, was a natural trumpet, probably available in either G or F, with mouthpipe shank and crooks (tons) down to D or C. 48 was a valve trumpet in F with fixed mouthpipe (no crooks) with a longer slide for Eb, but not indicated. It was the only trumpet available in the two lower grades, presumably to supply schools and lower ranked military organizations. 48B was the same trumpet, but with a tuning slide with rotary valve for the key change to Eb. 49 was likely a valve version of the natural trumpet, with crooks to D or C. Number 50, called “nouveau modèle, R. C.” was a C trumpet with fixed mouthpipe and longer tuning slides to lower the key to Bb and A. This new model was likely the introduction of a C trumpet with narrower bell flare (see image in the 1910 poster below) that continued in production until the late 1930s and re-introduced after World War Two. Earlier C trumpets, per the 1867 patent, had cornet bells. “R. C.” may have been the initials of a trumpet player associated with this design or some organization. As discussed earlier, the C and Bb trumpets with fixed mouthpipes were a new modification of Florentine Besson’s trumpet “à forme longue”, or “cornet-trompette”, both terms that she used for them in the 1867 patent. 50B was the Bb version of 50, with a cornet bell design, the modern trumpet that is now heard around the world.

Number 51 is described as a cornet from C to A natural or Ab and A natural, high. This is hard to understand, but may be related to number 50 in that it might have been a modification of the “cornet-trompette”, but with a cornet mouthpipe and mouthpiece receiver. 52 is equally hard to understand without an surviving instrument or image. It may have been a bass or tenor trumpet in G with crooks or slides to B and another choice in Bb and A natural.

In addition to Besson’s cornets and trumpets, they made a wide range of band, orchestra and signal instruments. This included soprano and contralto flugelhorns, altos, baritones, basses, contrabasses, ophicleides, numerous horn options with and without valves, valve trombones, slide trombones, fanfare trumpets, clairons, hunting horns, the family of cornophones and saxophones.

In Paris, the name F. Besson was retained long after Florentine’s death and that of Adolphe Fontaine, and as a brand name, is still in use. Besson was again a member of the jury for the Exposition Universelle in 1910, this time in Brussels. Capitalizing on the opportunity for promotion, they produced an extensive catalog with accompanying poster, seen below, with images of most of the brass instruments that they produced. Also included were products of other makers that they were marketing, including woodwinds, percussion and string instruments. Most of the cornets were listed at the same prices and model numbers as in the 1893 catalog. Notice on the poster, the company name is “F. BESSON (Mme F. BESSON)". This also appeared on the company letterhead used by Meha and she signed her letters “F. Besson”. The second page of the 1910 catalog included the following: “Through the brilliant services rendered to the musical art, the F. BESSON house, whose management today belongs to the granddaughter of its illustrious Founder, is at the head of instrument making in the world and its efforts will always tend to remain faithful to the principle that has made its great success: that of giving full and complete satisfaction to its numerous customers.”

On page 5: “Cornets à Pistons”, the Bb cornets are listed. The model numbers and prices are the same as in the 1893 Eugène Thibouville catalog. Some of the descriptions differ, but all evidence indicates that they are the same seven models. On age 6, the list of “Cornets spéciaux” had changed a bit. The first three cornets are the same, but 13, a cornet is C is no longer available in French model, but English only. Number 14 is now the cornet with a fourth piston for pitch change, now available either in C descending to Bb or in Bb ascending to C. 15 and 16 are the C cornets with rotary valve key change to Bb in the tuning slide, available in English model only, but with Desideratum of Concertiste valves respectively. 17 is the C cornet with two rotary valves in the tuning slide and also included the “echelle” extension to Bb. New to this list is the “Cornet-Trompette”. No examples of this instrument are known, but the author speculates that it is the same as the C trumpet below, number 30, but with a cornet mouthpipe and receiver for cornet mouthpiece and, perhaps, a different bell. Number 19 is the same echo cornet as in the 1893 catalog and enough examples survive to know that this had the Concertiste valves (from the early 1870s, not patented) as standard.

The list on page 8 of “Trompettes d’Harmonie”, the F trumpets (numbers 25, 26 and 27) were still listed first, with the Bb trumpets (31 and 31b) last. It’s possible that this was an old habit that didn’t reflect the market changes. Or, it was a turning point that they hadn’t predicted, with the Bb trumpets outselling the others by a very large margin in the coming years. The natural trumpet is no longer listed. The three F trumpets, numbers 25, 26 and 27 appear to be the same three listed as numbers 48, 49 and 50 in the 1893 catalog. Number 28 is the small D trumpet with slides for Db and C, that is conveniently illustrated on the poster. 29 is the smallest trumpet offered, in high F with slides for E, Eb and D. The translation of the additional description is: “Trumpet created especially by the company for the (works of Bach) Special mouthpiece.” It is the only instrument that was described as having a special moutpiece, presumably with a shallow cup for more ease of high notes. 30 is a C trumpet with additional slides for B, Bb and A, as illustrated, the same as 50 in 1893. 30a is in C only and could be further economized without a water-key. 31 is the Bb trumpet, as illustrated, with a longer slide for A, is the same as 50B in 1893. A less expensive version is listed, again, most likely for the student and military. 31B is the same Bb trumpet, but with rotary valve in the tuning slide to change to A.

A final price list to be considered here is from shortly after World War One and only a list of cornets and accessories. It appears typewritten and was copied by mimeograph or similar method. It states at the top that prices were raised by 40%, although a comparison to the 1910 prices show raises of between 233% (echo cornet) and 382% (number 2, perce pleine). Presumably, there had been at least one other price increase in between. Other than the price increases, it lists the same 17 cornets with the same model numbers as the 1910 catalog.

More history of the Besson company can be found in a very well researched and written 2016 dissertation of Jocelyn Howell on the history of the Boosey & Hawkes company.