High Pitch, Low Pitch and Modern Pitch

I’m surprised by how often I find that brass players have never heard of high pitch band instruments before. I suppose that most are from a younger generation, further separated in time and of a culture that values history less than ever. I don’t even remember exactly how I learned that most bands played at a higher pitch until after World War One. I do recall that a fellow band member in high school had a very old trombone without a good seventh position. It was later that I realized that he had he had a high pitch trombone with a low pitch tuning slide inserted.

The purpose of this page is to give a simple explanation of what we might encounter in brass instruments made in the last two hundred years. The world history of musical pitch standards gets a bit more complex than most are interested in or have need to know. A thorough discussion of pitch was written by David James Blaikley and published in A Descriptive Catalogue of the Musical Instruments Recently Exhibited at the Royal Military Exhibition, London, 1890, starting on page 235. An Internet search brings up a couple of explanations from British perspectives and a Wikipedia page that seems quite good, but again, more information than is practical for most fans of brass instruments from this time period. And, as always, please don’t assume that I have the last word, even within these parameters and I request any advice in making this a better tool for this purpose.

I’ll start with the most simple explanation: Military and Civic bands in the United States and most other western countries played at a higher pitch than Modern Pitch (A=440Hz). I variously hear others state that high pitch was A=452Hz or A=457Hz and that aligns with my experience with the actual instruments as well, although mostly closer to the lower of those. This applies to brass (and presumably woodwind) instruments used in the US after about 1850. I have less experience with instruments from before that date, but most are at a lower pitch, seeming very close to modern pitch, if they haven’t been modified. Indeed, many get modified as seen in the Bb cornet by Adolphe Sax featured on this site. The vast majority of brass instruments that we deal with were made after 1850, so of less concern for most collectors and players.

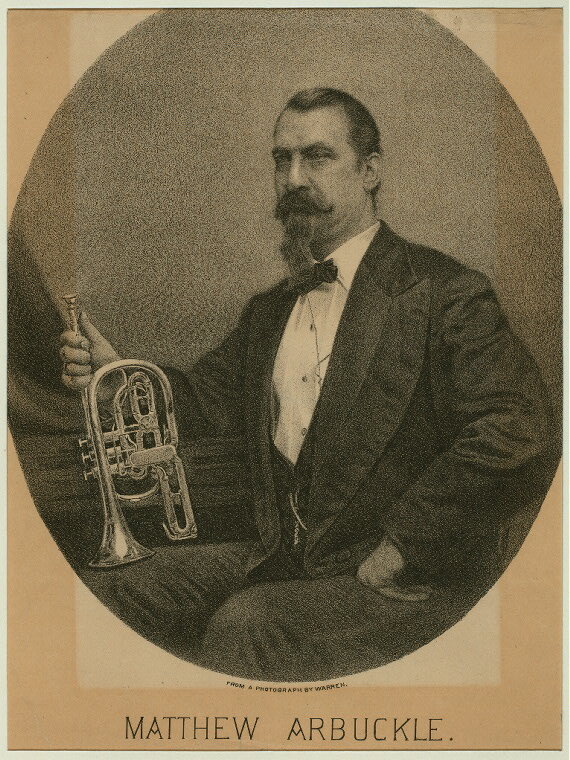

Also, right about this time, a number of western European countries agreed to a standard pitch at A=435Hz, almost exactly a half step lower than the common high pitch. This became somewhat standardized in orchestras in the US as well, being largely made up of immigrants from Europe. This was often called “French pitch” and eventually adopted by the bands of Patrick Gilmore and John Philip Sousa by the 1880s. The reason for the relatively early adoption of a lower pitch by these two bands was to accommodate vocal and violin soloists that were often featured. These musicians were from the world of the philharmonic orchestra and opera stage and not willing to sing/tune to the high pitch of most bands. In most photos of cornet soloists from the 1870s and later, we see the A shank in place in order to play in low pitch Bb. The lithograph of Matthew Arbuckle below is an early example, after he joined the Gilmore Band.

Matthew Arbuckle with his Fiske cornet in about 1870.

An early example of a cornet supplied with attachments for playing in lower pitches is seen below. This Bb cornet made by E.G. Wright before 1870 has a longer tuning slide for playing in either high pitch A or Bb at A=435Hz. In addition, it has a bit that can be inserted in the Bb shank, in combination with the shorter tuning slide allows tuning in between high and low pitch. The large, round mouthpipe crook is for G. Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory continued this practice through the 1870s and by 1880 it was quite common in higher quality cornets, typically supplying two bits of different lengths. Shortly after, the bits were dropped in favor of supplying a longer tuning slide intended for low pitch Bb rather than high pitch A. John Heald went his own way in the 1890s, supplying his Bb cornets with three different length mouthpipe shanks in addition to his patented tuning slide that telescopes out to A.

Bb cornet by E.G. Wright, made ca. 1868.

The next two photos are of Bb cornets by Frank Holton, both typical of their times. The first, made in about 1905 with mouthpipe shanks for Bb and A and tuning slides for high and low pitches. The second cornet, made in 1915, incorporates a slide with a stop rod for quick change from Bb and A (wider slide, stop rod hidden from view) and additional tuning slide and valve slides for tuning to low pitch Bb. In each tuning (high or low pitch) the valve slides would have to be drawn out to play in A.

Holton Bb cornet made about 1905 with low pitch tuning slide and mouthpipe shanks for A.

Holton New Proportion cornet in Bb and A, high pitch and low pitch, made in 1915.

Of course, Bb trumpets were becoming much more popular after 1900 and most were supplied with both high and low pitch slides. The Conn trumpet below, made in 1911, has its high pitch slides stored in its carrying case.

Conn New Wonder trumpet, 1911

I couldn’t resist showing this last example to illustrate the extreme that a US maker went to. This cornet, made by Harry B. Jay in Chicago in about 1915, with all the slides needed (17 in all) to play in C high pitch, C low pitch, Bb high pitch, Bb low pitch and a quick change to A (or B-natural with the C slides).

Cornet by Harry B. Jay, made about 1915 in C, Bb and A, high pitch and low pitch.

Because the low pitch, prior to 1919 was lower than modern pitch, with the low pitch slide installed and pushed all the way in, they are often lower than A=440Hz. If the high pitch slide has tubes are long enough, it can often be pulled out for modern pitch, on a Bb cornet or trumpet, usually about 7/8” each side. Otherwise, the longer slide would have to be shortened or a new intermediate slide made. In the case of Bb cornets with mouthpipe shanks, an intermediate shank can be made, such as John Heald had supplied in the era.

After World War One, the Treaty of Versailles included an international pitch standard that still holds today. Of course, this is A=440Hz. There was a lag time for most of the many thousands of bands around the world that were playing in higher pitches that couldn’t afford to make a sudden change. In the US, it happened fairly quickly, most changing well before 1930. Other regions, including most brass bands in Britain, Australia and southern Germany, among others, didn’t make the change to modern pitch until after 1960. Of course, less wealthy areas, including in Eastern Europe, Mexico, etc. this stretched into the 1970s or later.

I suppose it makes sense that after 100 years of pitch standardization, we shouldn’t be surprised that young musicians in the US have never heard of a time that it was otherwise.