Orchestral Trumpets in G by Antoine Courtois

While visiting a collector and accomplished trumpet soloist in Paris, I was able to examine three beautiful 19th century trumpets by Courtois: a natural trumpet from the 1880s, an English slide trumpet from the 1870s and the most spectacular is a valve trumpet from 1863. The latter was presented as first prize to the winner of the annual trumpet competition at the Paris Conservatory, Emile Laurent. This annual tradition dates at least to the 1840s. Click on images below for larger views.

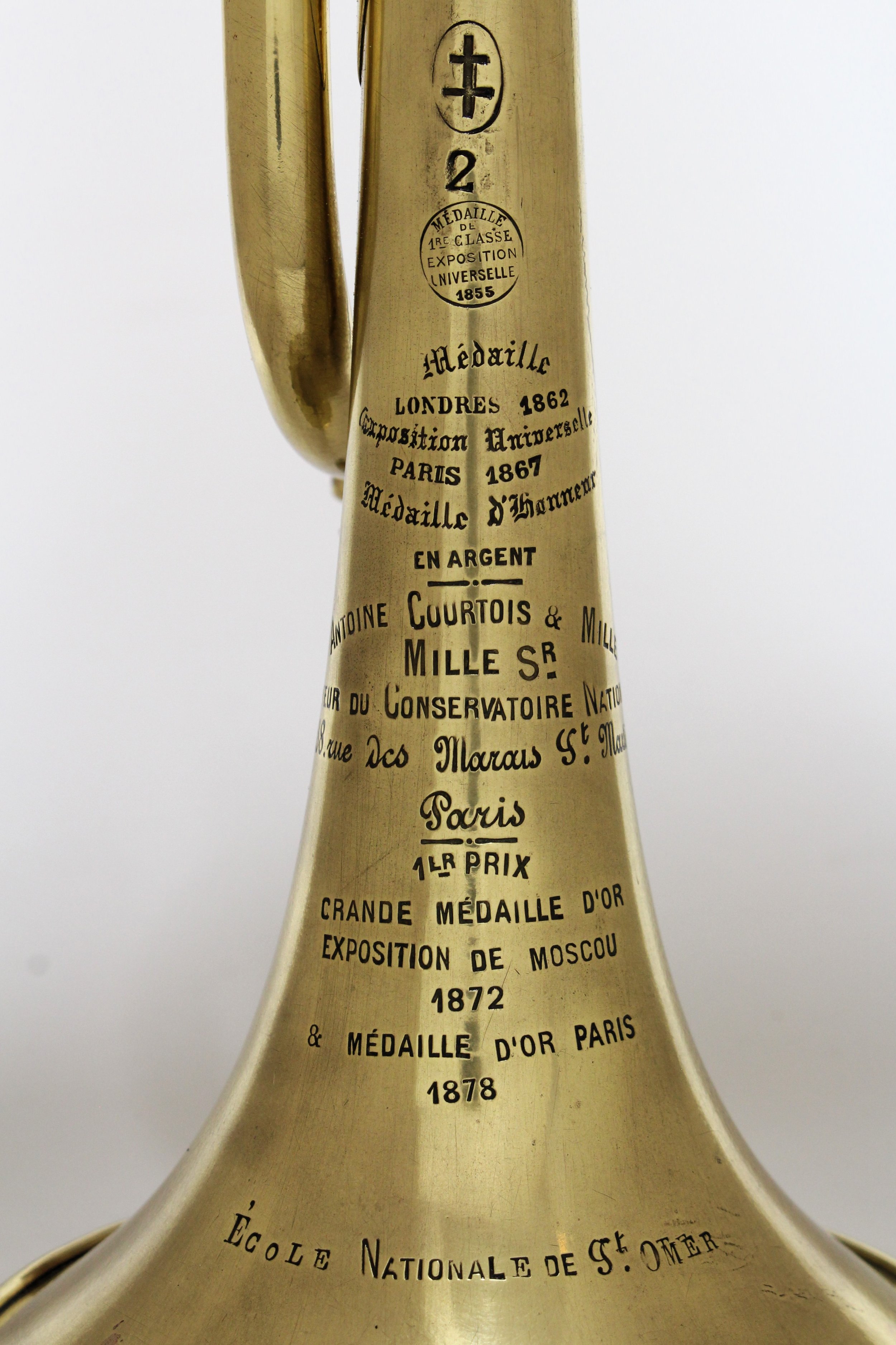

He had a fourth Courtois trumpet that was in rough condition, missing its pistons and other valve parts and all its crooks although all four slides were intact. As rare and valuable as these are, he had already been told that this would cost more to restore than its value after restoration, so he was interested in parting with it. Photos below show it before and after restoration, including a case similar to originals. Since this was a retirement project, the number of hours involved were not of consequence. All the replacement parts were made new based on measurements of originals. A set of pistons were borrowed from another collector to be sure of accuracy. Since the pistons are new and fit as new, this trumpet is an excellent player. According to the stamps on the bell, it was made for École Nationale de St. Omer, a secondary school in St. Denis, Paris between 1882 and 1889. Since the original valve caps are missing, we will never know the serial number, but it would have been between 550 and 700.

Below are photos of a Courtois trumpet that I first saw in 2017 in Arnold Myers’ office, while visiting Edinburgh during the joint meeting of the AMIS and Galpin Society. Since it had a very early serial number, Arnold was interested in adding it to his very important collection. He asked my opinion on it, without giving me any clues and I immediately recognized the valve section as being from a 19th century orchestral trumpet, probably in F or G. Obviously, Arnold already knew that it had been remodeled into a cornet in Bb at some time after F trumpets were obsolete and unwanted.

More than three years later, I got an email from Scott Smith, expert on early Courtois trumpets, with a photo of the same instrument. He was interested in converting it back to its original form. These orchestral trumpets made by Courtois in both F and G, were the standard for orchestras in France, Britain and the USA. They were copied by many other makers, although all the copies that I’ve seen were in F. This is an early example, having been made about 1870 and the fifth oldest valve trumpet by Courtois that we know about.

Once I had the silver plating stripped, I spent quite a bit of time looking for any evidence of its original form. I was quite confident that it had been in either F or G based on the dimensions of the bell and valve bore. I’m fortunate to have taken a lot of measurements of one in G that was owned by Dr Richard Birkemeier (now Barry Bauguess) that I had worked on several times. That trumpet is shown below with the E natural crook inserted.

Courtois G trumpet #670 with E crook, made about 1880.

I was unable to find any traces of original braces or the like to be sure the original pitch, but as expected, the valve numbers are visible where they had been covered by the cornet bell braces.

Valve numbers visible where they had been covered by the cornet bell braces.

During this investigation, I was able to determine that it had been rebuilt as a Bb cornet a second time and probably had a longer life as a cornet than as a trumpet. The bell stem had been badly damaged, at which time the long tapered ferrule was installed to cover the damage and connect it to the tapered curved tube (where the bell curve would normally be). It was then polished and silver plated again. This additional rebuild may be the reason that the original traces of soldered connections were completely obliterated.

Without any ability to say what the original pitch was, Scott decided to assume that it would have been that of the most common. Of the twelve of these trumpets known, only two are pitched in F, all the others in G. He decided that he wanted crooks to play in F, D and C and would not likely ever have reason to use it in the lower pitches. Of the Courtois orchestral trumpets that have been examined by the author, all are primarily in high pitch, about A=452Hz. This seems surprising, since we expect that the primary use was in symphonic orchestras that played in low pitch. Only a rare few have survived with all original equipment, but at least one has bits to lower the pitch. There is always more to be learned about pitch traditions.

The rebuild included plating and refitting the valves, which were too loose to be very playable. Since this is a largely non-original historical instrument there was no reason to hesitate in making that change. Notice that the valve guides are screws in the lower portion of the valve casings. This was already an archaic design by the 1870s and later trumpets have guides at the top of each piston as seen in Besson trumpets and cornets and many others.

The rest of the rebuild was fairly straightforward, but very time consuming. All of the main tubing that appears to be cylindrical is actually slightly tapered. If I were to make all these tapers, including the shank and crooks, by drawing them on steel mandrels, it would have involved making nine new mandrels. Instead, I used a technique that I learned from a German brass repairman who visited my shop many years ago while he was a journeyman. Starting with an annealed tube of the largest diameter, it is pulled through a drawplate, starting straight, but increasing the angle until the end. It is impossible to make precise tapers by this method, but with more annealing, manipulation and then burnishing it straight and smooth, one can get very close.

Of course, the valve slide tubes were all too short, so I used those from the third slide for the first and then made new tubes for the longer third slide. Since the second outside tubes are silver soldered to the casings, I couldn’t remove them without damage, so they had to be left at the Bb length. I shortened the tubes from the first slide to make longer second slide tubes at the G length. Then, since pulling that slide out for C and D was precarious, I made a whole new second assembly for C which easily could be pulled out for D.

Scott supplied an original nineteenth century Courtois trumpet mouthpiece so that I could make the shank and crooks fit it perfectly. Modern trumpet mouthpieces don’t insert as far but still work quite well and it plays especially good in G with a large rim diameter, like a Schilke 20 or Bach 1. Additional crooks can be made for this trumpet in the future. The originals had crooks down to Bb. The finished trumpet, without shank or crooks is 19 5/8” long (copied from the Birkemeier/Bauguess example, the St. Omer trumpet is 19 3/16” long), the bell rim diameter is 4 15/16” and the valve bore measures .454”. All of the trumpets made by Courtois before WWI that I have examined have bore size of about .453” or .454” (hard to measure precisely). This is roughly 11.5mm, a size used by many trumpet makers throughout the 20th century.

One last photo below is of a very similar orchestral trumpet belonging to Chris Belluscio (this one having received a rather rough restoration). We had assumed that this was another pitched in G and the newly made crook that Chris had received with it seemed to be for high pitch Eb. Once I mocked up a shank to put it in G I realized that it was actually pitched in Ab. It was only after that, that I compared the measurements to the G trumpets and indeed, it was shorter in most dimensions. Although I haven’t seen literature that Courtois also made these in Ab, I found no evidence that it had been modified from one in G or F. Chris may never need a trumpet pitched in Ab, so he had me make the crooks for G, F and Eb as you see in the photo below.

Courtois trumpet in Ab #510, made about 1875, with crooks for G, F and Eb.