The History of the Modern Trumpet

Or “Get that #@$%&! Cornet out of my Orchestra”

Besson trumpet, about 1920.

First, I must state that thoroughly covering this topic is too complex for a short essay and I’m not the most qualified person to write a definitive history. Rather, my intention is share my point of view and tidbits that come from my particular familiarity with the instruments. My interest has recently been sparked by conversations with other knowledgeable people and some research connected with assembling pages for my website. In this, I hope to spark some interest and possibly a conversation with the reader. In other words, approach this as a work in progress and let me know where I’ve made mistakes or have left something out, hopefully leading us to a better understanding of the subject and a document that we can share with those interested in learning.

The time period of gestation for the “Modern Trumpet” is roughly 1815 to 1910, or from the invention of a workable valve for brass instruments to the explosion of popularity of the French style Bb trumpet. I know that there may be discussion on the topic of what is the ultimate modern trumpet, but it seems very clear to me that the modern piston valve Bb trumpet, with many slight variations, being made by all the large makers and most of the smaller makers is almost universally used around the world. Trumpet players tend to focus on the diversity among the many choices, but when compared to other brass instruments, especially tubas, modern trumpets are amazingly generic.

The subtitle may not at first seem appropriate, but comes from a thought that struck me: the modern, French style Bb trumpet was developed, more or less (I believe more), as a substitute for the use of cornets for performing the trumpet parts in symphonic orchestras. There certainly are cornet parts written into symphonic scores, especially in French Romantic music, but by and large, the trumpet was the soprano brass of choice even when cornets became available.

Hector Berlioz, who at a time when trumpets and cornets were very different instruments, very often included cornets in his scores, stated in his treatise on instrumentation in 1855: "A phrase that would appear tolerable, when performed by violins or the woodwind, becomes flat and intolerably vulgar when emphasized by the incisive, brash and impudent sound of the cornet."

Much later in the century, a similar, but more strongly critical comparison to the orchestral trumpet is expressed by Ebenezer Prout, professor of music in the University of Dublin, in “The Orchestra, Volume 1. Technique of the Instruments”, published in London in 1897: “The tone of the trumpet is the most powerful and brilliant of any in the orchestra…Its quality is noble and it is greatly to be regretted that in modern orchestras it is so frequently replaced by the much more vulgar cornet. The tone of the cornet is absolutely devoid of the nobility of the trumpet, and, unless in the hands of a very good musician, readily becomes vulgar. It is, however, so much easier to play than the trumpet, that parts written for the latter instrument are very often performed on the cornet. In some cases, especially in provincial orchestras, this may be a necessity, as it is not always possible to find trumpet players; but it is none the less a degradation of the music. We cordially endorse the dictum of M. (Francois- Auguste) Gevaert, who says—‘No conductor worthy of the name of artist ought any longer to allow the cornet to be heard in place of the trumpet in a classical work’”. The trumpets described and illustrated there are pitched in G and lower, with and without valves. Even at this late date, he makes no allowance for the possible use of trumpets in Bb or C even though they were becoming common. These are fairly strong words, and while the sentiments may have been held by some, and possibly many, in the world of symphonic music at the time, it is surely a resistance to a change that was already well under way.

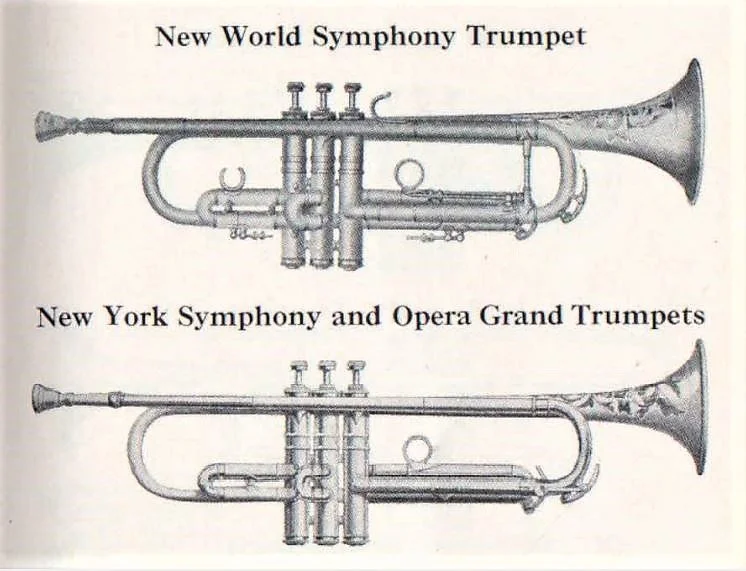

Images of trumpets in Prout’s “The Orchestra”.

The long trumpets in F and G were disappearing from the scene and mostly used in the older and more conservative organizations. Indeed, at its founding in 1891, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra brass section included two cornet players and two trumpet players, although by the end of the decade they were all described as trumpets. I can only guess what trumpets they had at their disposal, but my suspicion is that it was F trumpets at the start and Bb and C trumpets a decade later. A Chicago Tribune columnist, in 1902, writing about a performance of Bach's D Minor Mass, indicated that Theodore Thomas "had solved the perplexing trumpet problem" by covering the (three) trumpet parts with six trumpets augmented by six clarinets. Perhaps these examples indicate the limitations of both instruments and performers of their times, but also a deep rift, culturally, between trumpets and cornets, even if performed on by the same musicians.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, there was a great increase in the demand for proper symphony orchestra performances. Only a few orchestras had existed in the US previously and the only source for classical music for most of the country was as played by brass bands, in church or in the parlor by family and friends. Europe had long established classical musical organizations but there too, a growing and more educated middle class had a hunger for culture.

Some cornet players took up the trumpet, but for the most part orchestras in smaller metropolitan areas would have great trouble finding musicians or even the correct instruments for them to play. In 1869 in New York City, Theodore Thomas hired the world famous Jules Levy to play cornet in his Summer orchestra concert series. Thomas didn't think much of the cornet as a substitute for the trumpet although he didn’t complain about the increased ticket sales and Levy was hired as a cornet soloist and not a member of the trumpet section. In London, Levy had played in orchestras of the Royal Opera House and Crystal Palace Promenade Concerts, although I haven't been able to find out if he ever played the trumpet in those situations.

It is well known that the Bb trumpet was widely adopted in Germany, Austria, Prussia and other eastern countries long before the rest of the world, but I was surprised by how early some existing small trumpets were made and even more commonly included in very early price lists. A good surviving example from about 1837 is a two double piston valve trumpet made by Andreas Barth, Munich in the Utley collection. Two earlier examples of similar design have fixed half tone crooks indicating that they were intended to play in Bb only are one in the Stadtmuseum Nördlingen (Bavaria), is engraved with the date 1828, made by Michael Saurle and another in the Beyerisches Nationalmuseum by J.G. Roth that might have been made in the early 1820s. A very interesting two valve Bb trumpet that was likely made later is featured on another page on this site.

There are a few trumpets in high C and even D in price lists of Leopold Uhlmann and Joseph Saurle before 1850. By the late 1850s Bavarian maker Ferdinand Stegmaier lists high Eb and F trumpets (each with one crook for additional pitch). Most of these very early (before 1860) small trumpets came with three or four crooks making me believe that they were intended for the orchestra rather than the military band. In contrast to this fact, most existing very early Bb and C trumpets appear not to have been supplied with crooks. There are several explanations for this apparent contradiction. The most likely is that the biggest demand was by military and civic bands where they weren’t as likely to be required to play in a variety of keys. So a maker listing two Bb trumpets, one with crooks and the other Bb only may have sold 100 of the latter for every one of the former. Survival rate for such rarities can’t be used as a firm measure of original numbers either, but rather as an indicator of possibilities. The other explanation is that many instruments are modified for a variety of reasons. Most often it is in an attempt to repair damage or loss of original parts but also to fit a different mouthpiece or change the pitch. Many F trumpets were shortened to make Bb trumpets and even cornets.

Unknown German maker, about 1850, showing Bb trumpet (13).

In his very comprehensive "Das Ventilblasintrumenten", Herbert Heyde has thoroughly studied these instruments including the occasionally used term "trompetina" as applied to the early small trumpets. He makes a good case for the connection between these and the French cornets à pistons, but it seems one of coincidence of inspiration rather than a direct cultural connection. He determines that the small trumpets were earliest used in southern Germany, Austria and Italy (cornetto a pistoni with rotary valves) that both in the particulars of design and name, they were somewhat variable depending on local traditions. By 1860, they began to supplant the G trumpets in military bands in Prussia, and by this time, the French cornets were a distinct tradition and the Germanic Bb trumpets were eventually embraced by almost all of eastern Europe.

In part of my research for this essay, I made a list of all the early examples of high trumpets (Bb, C and smaller) that I could locate and also those in catalogs and price lists from the time, even though you might say that most (all?) of them are not within the direct lineage leading to the modern trumpet. A clear example of this fact are the very small bore double piston valve Bb and high Eb trumpets made in the US that were known as post horns. These were almost direct copies, although with even smaller bores, of small German trumpets (sometimes called trompetina). They were completely abandoned in favor of keyed bugles, cornets and Saxhorns by the mid-1850s.

Graves & Co. post horn in Bb, about 1843.

A singular example of a rotary valve trumpet made in Boston by E.G. Wright in about 1860 has the general appearance of a German Bb trumpet. This form was generally known as cornet in the US, including in the D.C. Hall (also in Boston) catalog of 1864, but I judge this one to be a trumpet because it retains its original mouthpiece that is very much different from those supplied with cornets, that is very trumpet like in form. It also has an original crook for the key of G and would have originally had one for Ab and shanks for Bb and A and possibly larger crooks for lower pitches. The more important progenitors to our modern trumpets were the longer instruments (mostly in G and F with crooks for lower keys) that the music was written for, but for this essay, I am interested in the early origins of the small trumpets that existed alongside the cornets in the same keys.

Another Bb cornet in trumpet form advertised in the Boston Register, 1862

It seems that the small trumpets were slower to arrive in France and even more so in conservative England. The very wide acceptance of the cornets à pistons covered most of the musical territory that trumpets did in the east and the casual observer might justifiably think that it is a distinction without much difference. If the largest difference between the two is the shape of the mouthpiece cup, then we can’t comment without making a study of the mouthpieces used and mouthpieces are harder to assign date, geography and purpose than the rest of the instrument. In most cases, antique brass instruments survive without original mouthpieces. Not surprisingly, I don’t find as many examples of French small trumpets (Bb and higher) in either catalogs or collections.

In the catalog of the Parisian music dealer Husson & Buthod from about 1850, is illustrated a trumpet with three Berliner valves. This appears to be in Bb or C but could be in Ab or G and is not described except to call it a trumpet. It came with one shank and six crooks, which is the evidence that leads me to believe that it was in one of the higher pitches, and lowering the pitch to D or C.

Image from Husson & Buthod catalog, about 1850.

Gautrot Aine & Cie was the largest French brass instrument maker in these years and may have supplied that instrument. But in Gautrot’s very extensive catalog of 1867, offering many choices in cornets and Saxhorns, they only offer trumpets in F and G with crooks to C. They did offer two styles without valves as well as the choice of Stoelzel, Berliner and Perinet valves. Gautrot’s successor, Couesnon still had the same offerings in their 1889 catalog. All of these are called “trompettes d’harmonie”, distinguishing them from the band instruments.

Images from Gautrot aine & Cie catalog of 1867.

The smaller Parisian maker, Courtois, made a specialty of supplying expensive (generally costing 40 to 50% more) instruments to the most discriminating customers, including the Conservatoire Nationale. Richly decorated trumpets in F were awarded to the student judged to be the best trumpet player each year. Examples are preserved in the Paris Musee de la Musique. Their Perinet valve F and G trumpets were widely copied by other makers in France, England and Germany (for export). Of course, there were instruments available that were not illustrated in the catalogs. In 1861, Courtois made a trumpet in high D for Belgian Conservatory cornet teacher Hippolyte Duhem, presumably for playing the high trumpet parts of Bach and Handel, which were enjoying a revival. This may have been similar to the one that was illustrated in the 1885 catalog and there is a C trumpet of this general configuration in Arnold Myer's collection at Edinburgh University that was made in about 1874 and retains its original tuning slide extension for Bb as well as Bb and A shanks and crook for Ab.

Image from Antoine Courtois’ catalog of 1885.

Both Mahillon and Besson also made trumpets in high D by this time for the same purpose. Courtois also made small trumpets in Bb with double piston valves, very much like the “post horns” made in the US that are discussed above. An early example, likely made in the late 1840s with “Mainzer” lever mechanism, is preserved in the Paris Musee de la Musique and another, made about 1875, with Belgian style pushrods is part of the National Music Museum’s Utley collection. The latter has Bb and A tuning slides, but it doesn’t appear to have had crooks for lower keys. This was sold new in London, which is interesting in the fact that a few decades later, Belgian Bb trumpets (with Perinet valves) were used in some English symphonic orchestras. Sabina Klaus reports that it retains a (likely original) mouthpiece adaptor to fit a cornet mouthpiece, indicating that it was used as a cornet as well. This became a common feature of Bb piston valve trumpets made in the US in the 1920s and 1930s, but was not known to be common in the 1870s. Adolphe Sax also made small Bb trumpets in the “Mainzer” style in the 1840s as well as high Eb and lower pitched examples as used by the Distin Family Quintet.

In their 1897 catalog, Courtois was still offering their famous F trumpet, but also a small C trumpet with crooks for Bb and A . The C trumpet is not illustrated and I suspect that it continued in the form of the D trumpet illustrated in the catalog of 1885 shown above, with the mouthpipe directly entering the first valve rather than extending to a tuning slide that leads to the third valve as in our modern C trumpets. This is true of the 1875 Courtois Bb trumpet mentioned above and the earliest known Besson Bb trumpets known (from about 1875 also) as well as the Belgian style trumpets that were used in that country until mid-20th century.

By the early 1900s, Courtois was making trumpets in Bb, C and D that are very much like our modern instruments other than being smaller through the bell flare. By 1919, the Courtois Bb trumpets had bells of proportions very similar to those made by Besson. Judging by the number of instruments made in the mid-20th century that have survived, Courtois must have competed fairly well with Besson for the trumpet market in the years between the wars, even though Besson is remembered as being much more important.

In England, the slide trumpet in F (with crooks to C) dominated the orchestral scene, its use starting in the late 18th century and still used into the 20th by some players. This is arguably the trumpet most similar to the trumpets of the Baroque era and before and yet there were moves to modernize the trumpet in England as well. The best known maker of the English slide trumpet, Kohler (London), began making two unique designs with three piston valves, patented by John Bayley in 1862: the Handelian Trumpet (in F) and Acoustic Cornet (in Bb). See: "The Kohler Family of Brasswind Instrument Makers" by Lance Whitehead and Arnold Myers. Both of these had fixed, tapered mouthpipes instead of being cylindrical with terminal crooks to change the pitch as in almost all other trumpets from this time. Both of these instruments utilized alternate tuning slides for playing in lower keys and fit mouthpieces with cornet shanks. They looked very similar in layout, the trumpet having an extra loop of tubing and the cornet being very much like the modern trumpet with the tapered mouthpipe leading directly to the tuning slide and then the valves and bell. These instruments didn't catch on and later "Handelian Trumpets" by Kohler were in Bb with cylindrical mouthpipes.

It is widely understood that the Besson Bb trumpets were the benchmark design that all modern makers copy to one degree or another. Perhaps, with our dizzying array of models of very similar design available to us, it is more accurate to say that they are copies of copies. Early trumpets by Bach, Olds, Conn and other makers, introduced in the first 30 years of the 20th century, look very much like Besson trumpets in basic shape and emulated the basic acoustical design, although had their own designs for decorative braces, caps, hooks etc. In the 1930s Benge started building trumpets that looked even more like those by Besson.

Holton trumpet made in 1912 is a close copy of those by Besson.

From about 1920, the large US makers also made popular models with very small bell flares for the (mostly amateur) dance band market that wanted a sound that deviated more thoroughly from the old fashioned cornets. This fashion was short lived and these trumpets were replaced around 1930 with narrow, "streamlined" (now sometimes called "peashooter) trumpets with small bell rim diameters that were in fact full size trumpets acoustically. These were popular with dance bands and jazz trumpet players, but disappeared from the market after World War II.

Conn 2B above, close to Besson prototype and skinny bell 24B, not likely used in the Symphony or Opera.

While most of the Besson inspired trumpets came on the market after the explosion in popularity after 1910, the demand for Bb trumpets in popular music had already been growing. In the US, this was due in large part to the fact that Sousa’s band was using them starting in 1892 and that John Philip Sousa was writing parts for them in most of his compositions for band. Before Sousa's professional band, Patrick S. Gilmore employed two or three F trumpets crooked to Eb. It is possible that in Sousa's first few years he followed this tradition, but only Bb trumpets are seen in photos. Before 1900, Sousa's trumpet players were playing Conn Perfected New York Wonder trumpets as pictured below. In an earlier photo of Sousa’s Band, the trumpets are not seen clearly enough to identify, but appear to be in Bb.

Trumpets used in Sousa’s Band, late 1890s.

The two largest US makers in the early 1880s, Conn and Boston, were offering F trumpets with crooks for lower pitches (examples by Graves and Wright preceding those as far back as the early 1840s). In 1884 Conn lists trumpets in both F and G with crooks in half steps down to C. Surprisingly, they also list a trumpet in (high?) D with shank for Db. As in Europe, Conn likely saw a demand for these trumpets for playing 18th century orchestral literature. The lack of crooks C and/or Bb limited their utility in contemporary bands.

Illustration from C.G. Conn’s “Trumpet Notes” of June,1881.

Boston also mentioned a trumpet in Bb in their 1887 catalog. Unfortunately, we don't know what the Bb trumpet looked like, but I would guess that it was very similar to the F trumpet shown below without the extra loop of tubing, which would make it very much like our modern trumpets.

Image from Boston’s 1887 catalog.

By 1899, Conn was making Bb trumpets that were clearly a development or re-arrangement of the Wonder model cornets including the 1886 patent valve design and distinctive bell curve. By 1910, they had modernized the look in parallel with the Perfected Wonder model cornets, sharing bore sizes and bell designs with them (which is confirmed by measuring).

J.W. Pepper and others were importing Bb trumpets of a somewhat different character, with long, cylindrical mouthpipes and very wide, almost flugelhorn looking bell flares and aside from a “shepherds crook” bell, they copied the Besson layout. The earliest Besson Bb trumpets in this mode were being made by the 1870s and also had the “shepherd’s crook” bell shape and removable mouthpipe shank to accommodate crooks for other keys. Looking beyond these differences, they were very similar in proportion to the modern trumpets: the mouthpipe was tapered and the bell was about the same length and with a similar flare.

The illustration below is from Besson's 1910 catalog, showing trumpets in Bb, C and D, very much the same as modern trumpets. The only Besson Bb trumpet made before 1905 that was closely examined for this article was made about 1897 and appears to have been modified from a C trumpet, so conclusions can’t be drawn from it. The mouthpipe and tuning assembly is from a later Besson Bb trumpet and it is also possible that the bell is not original. Another Besson C trumpet, made in the 1880s and appearing to be unaltered, looks very much like those made after 1910. I’m assuming that the pre-1900 Bb Besson trumpets (serial numbers before about 65,000) were very much like the later instruments that we are more familiar with although this is an important deficit in my discussion and additional data may alter my thesis. If any reader knows more here, I’d like to hear from you.

Image from Besson’s 1910 poster.

Noted paleontologist and collector of cornets and trumpets, Niles Eldredge, has made a study of Besson trumpets and cornets. He has been able to answer many questions, but even more questions have arisen. Niles is currently working on an article to be published in the Historic Brass Society’s Journal in which he will present what he has learned about Besson’s early trumpets. I look forward to filling in at least a few gaps after reading that. In my essay on the difference between the trumpet and cornet, I posit that the Besson Bb trumpet was a development or rearrangement of the parts of their cornets that they had been making for three decades by that time. The bell and valve section are very similar in dimensions. The major difference is in the shape of the mouthpiece cup, which would be more bowl shaped rather than the funnel shape of the cornet mouthpieces. What they created was an instrument with the easy playing qualities of the cornet but intended for playing parts written for the trumpet.

A promotional poster issued by the English Besson factory in about 1880, at the time still under the ownership of Marthe Besson, included a photograph of what appears to be a Bb or C trumpet in modern form except for the fact that it had removable mouthpipe shanks. The alternate shanks were presumably for additional pitches, but the name of this instrument, “trumpet-cornet” begs speculation that it may have been supplied with one shank for trumpet mouthpiece and another for cornet and may have been the first "modern trumpet" with cornet proportions. Confusingly, the 1910 Paris catalog offers a "cornet-trumpet" in C and Bb without illustration or further description. Besson (France) supplied both cornet and trumpet mouthpipe shanks with the pocket cornets in the 1920s and 1930s. The very maker that provided the prototype model for our modern trumpet didn’t avoid blurring the distinction between their trumpets and cornets.

Image of trumpet from Besson’s poster of about 1880.

After parsing the facts as best I can, I have concluded that the family tree of our modern trumpets is as complicated as those of most families. There were early trumpets, similarly sized to our modern trumpets and using similar mouthpieces that were played in both orchestras and military bands but are not directly linked by history or tradition. There are the longer trumpets which were developed from the tradition of valve-less trumpets, used in eastern European bands but mostly intended for the orchestral performance. These trumpets only passed down their literature and basic mouthpiece shape. Then there were the Besson small trumpets that got most of their “DNA” directly from the cornets. Only the basic mouthpiece shape was inherited from the traditional trumpets in an attempt to imitate the nobility of the trumpet sound with the easier playing qualities of the "vulgar cornet".